Across Georgia, longtime physicians, nurse practitioners and other health care providers are retiring at a faster pace than they are being replaced. For patients and communities — particularly outside major metro areas — that shift is beginning to reshape how and where care is delivered.

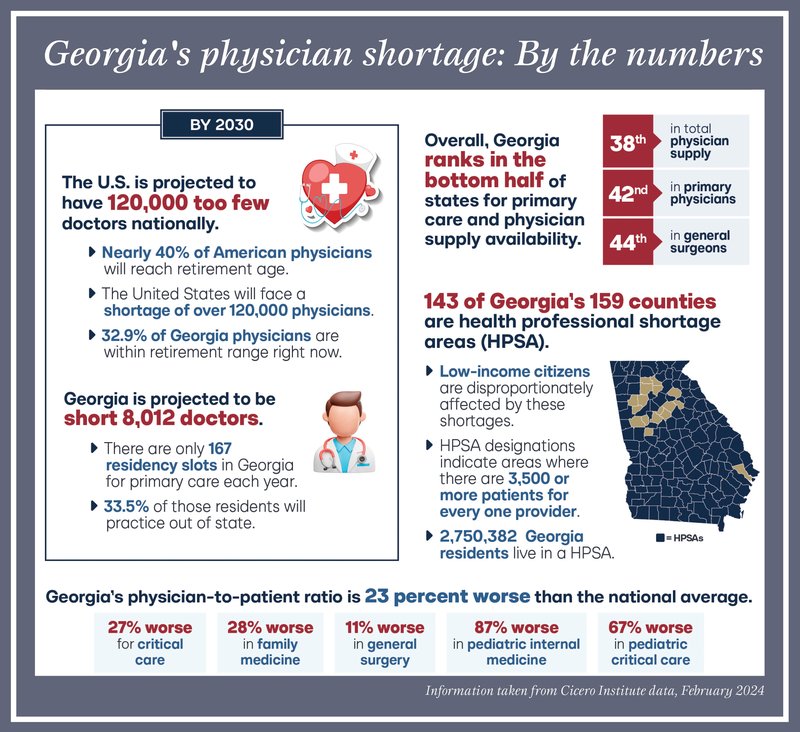

Georgia currently has about 28,000 practicing physicians serving a population of more than 11 million people. That translates to a physician-to-patient ratio that is roughly 23 percent worse than the national average, according to the Georgia Public Policy Foundation. Maintaining even that ratio will require the state to add more than 8,000 physicians within the next five years, including an estimated 2,100 in primary care alone.

The challenge is compounded by two forces moving in opposite directions: population growth and provider attrition. Georgia’s population continues to grow and age, which increases the demand for care. At the same time, many physicians who have been practicing for decades are reaching retirement age. As those providers step away, fewer new doctors are available to take their place.

State leaders have taken steps to address the issue. In recent years, Georgia has expanded opportunities for physician training by investing in graduate medical education, commonly known as GME. Lawmakers added $20 million to last year’s budget to fund grants for new GME programs at hospitals south of the “Fall Line Freeway,” which spans the width of the state, from Columbus to Augusta — a region that includes many rural and underserved communities and includes Bulloch County — and this year allocated $3 million to fund 150 new primary care residency slots.

The University of Georgia is also scheduled to welcome its first medical school class this fall, a move aimed at increasing the long-term supply of physicians trained in-state.

Additionally, in June, Georgia submitted a proposal to the federal government for $2.5 billion in total funding through a Directed Payment Program intended to support additional residency slots, improve physician retention and expand obstetrics and gynecology services statewide.

Even with those efforts, health care leaders acknowledge a fundamental timing problem. It takes an average of seven years of education and training for a primary care physician to become fully licensed and begin practicing independently. As retirements accelerate, that pipeline alone may not be enough to offset losses in the workforce.

As a result, many states are exploring ways to broaden who can deliver care — and advanced practice providers are playing an increasingly visible role. Nurse practitioners are permitted to practice independently in 28 states and the District of Columbia, while physician assistants have independent practice authority in eight states. However, Georgia still requires collaborative practice agreements with physicians for both roles, a structure that supporters say ensures oversight but critics argue limits access, particularly in areas with few doctors.

At the same time, small independent practices across the country are facing financial pressures that threaten their survival. Rising costs, reimbursement challenges and administrative demands have led many offices to sell to larger systems or close entirely, further concentrating care and reducing local options.

In Bulloch County, the recent retirements of multiple longtime providers — including Cheryl Perkins, Jean Bailey and Patty Law — are part of a much larger shift unfolding across Georgia. The impact is personal as well as systemic, leaving in their wake decades of service that cannot be quickly replaced.

While no single solution is expected to close the gap, state officials continue to weigh the options, guided by health care experts who stress that addressing the shortage will require a combination of training, retention and expanded utilization of qualified providers.